The broad group of fermented or raw sausages includes a large number of products whose characteristic properties are partially or completely dependent on fermentative action of certain types of bacteria. The comminuted meat mass may be submitted to curing either prior to or after stuffing. The stuffed sausages are processed by smoking, drying and ageing which make a product entirely suitable for eating without further cooking.

The principle two subgroups of fermented sausages are semidry or quickly fermented and dry or slowly fermented (semifermented) sausages. There are both hard and soft types in both subgroups.

Semidry sausages differ greatly from dry sausages by their pronounced “tangy” flavour of forced fermentation resulting in lactic acid accumulation and a bulk of other products of fermentative breakdown. The addition of starter cultures for a number of semidry sausages is particularly successful.

Semidry sausages are usually stuffed in medium-and large-diameter natural or artificial casings. The length of production (smoking and fermentation) of these sausages depends upon their type but rarely exceeds several days.

The pH of semidry sausages is explicitly acid (4.8 to 5.2–5.4); although they are often finely chopped and spreadable, many of them can be cut in thin slices; their water content reaches 35 percent or more.

Semidry sausages are regularly smoked and only exceptionally slightly cooked by the heat applied in the smokehouse at various temperatures, mostly not exceeding 45°C and very occasionally rising to nearly 60°C for a strictly limited time; after smoking the sausages are usually air-dried for a relatively short time.

Semidry sausages usually contain an important proportion of beef. Their shelf life is surprisingly good due to low water activity, accumulation of acids and smoke compounds, counteracting the effect of lactic acid bacteria on spoilage microorganisms, etc. A high level of hygiene and the ability to perform dexterously all operations in the manufacturing process are basic prerequisites for the good keeping quality of semidry sausages. Semidry sausages have improved stability if stored in the chiller, protected from humidity rather than at room temperature.

This category of sausages is popular in many European countries and North America. As these sausages need only little refrigeration, they can be successfully produced in many subtropical countries.

The main sausages of this group are: summer sausages (with a series of varieties in many countries), different types of cervelats and metwursts, lebanon bologna (in USA), etc.

The organoleptic and other properties of dry sausages depend not only upon the products of sugar bacterial fermentation but are also strongly influenced by biochemical and physical changes occurring during the long drying or ageing process. The use of starter cultures for this category of raw sausages is less successful than for the semidry varieties. The length of production, either with or without smoking, and drying periods depends upon a multiplicity of factors, such as diameter and physical properties of casings, sausage formulation, choice and methods of preparing meat, conditions of drying etc. but overall processing time may require up to 90 days. The final pH of dry sausages is usually somewhat higher (5.0–5.5) than in semidry sausages, and it increases during the second part of this long ageing process.

Dry sausages are made from selected, mainly coarsely chopped, meat (some Italian salamis, some types of sucuk); often they are moderately chopped (majority of small-diameter dry sausages) and very occasionally finely chopped. They are cut in thin slices, their water content is under 35 percent, but normally less than 30 percent. Most varieties of dry sausages are subjected to cold smoking (12 to 18°C) but sometimes not; in some countries they are often heavily spiced with red pepper or garlic or sometimes heavily smoked and strongly salted. In principle, they are processed by long, continous air-drying, sometimes after a comparatively short period of smoking.

The formulation, degree of grinding, level of fermentation, smoking intensity, temperature of ageing and type and size of casing as well as other factors determine the properties of the final product. Dry sausages are stuffed in both natural and artificial casings of varying diameters. In the preparation of dry sausages natural casings are preferred because they adhere closely to the sausages as sausages shrink. Sausages stuffed in casings with a diameter exceeding 4.5 cm are often called “salami”; salamis are chiefly made from coarsely ground meat, predominantly of pork and are not smoked. The shelf life of dry sausages is excellent, which may be especially attributed to the high salt-to-moisture ratio. These sausages are normally kept without refrigeration.

Raw sausages, which are not submitted to the smoking process, are known as air-dried sausages. This variety of dry sausage is characterized by a highly attractive appearance and by its yeasty-cheesy flavour. Air-dried sausages are marked with or without mould overlay.

The principle dry sausages are salami of different types produced in many countries followed by cervelats and many small-diameter dry sausages. Dry sausages may be hard, intended for slicing, and soft style sausages, which can be spread. An especially important fact in dry sausage manufacture is that the same raw materials, stuffed into different casings, give a quite different finished product. The wrapping of the twine on the sausage, contributing to the strength of the casing, is also of importance. Some large diameter sausages are corded with many loops and 3 to 5 longitudinal strands, while others have only circular twine.

Dry sausages are usually sold as new dry sausages (about 20 percent weight loss from original weight), moderately dry (about 30 percent of weight loss) and dry sausages (about 40 percent of weight loss).

The meat of adult, well-fed animals is preferred in raw sausage production. The use of chilled meat with a low pH is most suitable. For beef, the lowest pH of about 5.4–5.5 is obtained within a couple of days. Pork usually acidifies a little faster with final pH of 5.7–5.8. It is recommended to use meat that has been slightly frozen (-3° to -5°C) for one or two days prior to processing. The same holds true for fatty tissue. The use of beef is somewhat preferred for semidry sausages while pork seems to be more suitable for dry sausage manufacture.

All meats used in raw sausages need extra careful trimming of fat and sinews; soft intermuscular fatty tissue in particular should be thoroughly removed.

Spices contribute mainly to the development of flavour in dry sausages but it has been shown that they also possess an inhibitory and stimulatory activity, thus influencing the growth of certain bacteria. Of the bacteria studied, Lactobacillus plantarum was found to be the species most frequently stimulated by different spices with respect to growth and to acid production.

Methods of grinding and chopping vary widely with the different types of semidry or dry sausages. In a general way it can be said that the finer the degree of grinding and chopping the more complete will be the extraction of protein while the spreading or slicing properties of the finished product will be improved. The same is true for bacterial contamination. Beef is normally chopped first and then the pork components and other ingredients are added. Salt is added at the very end of chopping.

Fig. 24 RAW SAUSAGE PREPARATION IN THE CUTTER

(Photo courtesy of Kraemer und Grebe, GmbH & Co KG,

D-3560 Biedenkopf-Wallau, W. Germany)

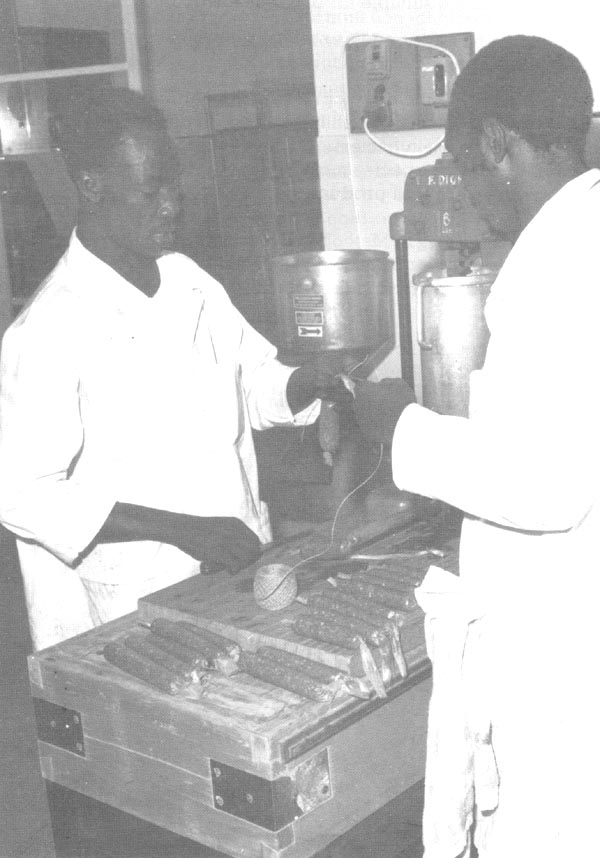

Fig. 25FILLING AND LINKING SAUSAGES IN SMALL-SCALE PRODUCTION

The chopped meat mass should be well mixed with other ingredients and should be either immediately stuffed or placed in shallow pans and held under refrigeration to enable the curing process and stabilization of microflora. The meat mix in pans must not contain air pockets which are excluded by kneading; at the same time, the meat should be covered to eliminate its contact with air.

After remixing again in the mixer, the meat mix is packed in the stuffer as firmly as possible to exclude air pockets. Stuffing into casings should also be done firmly and carefully to exclude air. Air inside the casing will discolour the meat and reduce the shelf life of the sausage. After the sausage has been stuffed, the open end is tied (or clipped) and a loop is formed so the sausages can be suspended on rods. The air pockets under the casings are punctured wherever they are visible to eliminate air.

Raw sausages have historically been produced in natural casings. Many of them are identified by the casing used or by the manner in which string is tied around them. Casings, natural or artificial, should be prepared with great care. Sewn beef casings are also used for some large diameter semidry sausages.

The stuffed sausages are placed in a special place or room to enable the surface moisture to escape. The optimum temperature of this preliminary drying varies from 20 to 23°C and the relative air humidity should not exceed 75–80 percent. The sausages must neither dry too fast nor retain surface moisture and become slimy. Another alternative is to hang the sausages overnight in a chiller at 6–8°C. If the sausage casings are overdried, smoke will not penetrate.

Only hardwood sawdust smoke is applied. Uniform distribution of temperature and smoke throughout the smokehouse is essential. There is no standardized procedure for smoking different raw sausages. Sausages are smoked from several hours to several days or weeks according to the diameter of the product: small diameter sausages, from 10 to 40 hours; medium diameter sausages, 15–45 hours; and large diameter sausages, several days and exceptionally 1–3 weeks.

In traditional smokehouse, uniform distribution of smoke throughout the smokehouse can be achieved by the appropriate distribution of the fire pits in different parts of the smokehouse. In a modern well-designed smokehouse, the smoke density and its distribution are maintained at the required level with equipment provided for controlling circulation, temperature and humidity. While liquid smoke solutions are commonly used in many meat products, the use of liquid smoke sausage manufacture is not really consistent with traditional practices.

The smoking of semidry sausages differs from that of dry sausages.

Semidry sausages are usually smoked at a higher temperature (22–32°C or above) and a heavier smoke is usually applied. During smoking or prior to smoking of semidry sausages the fermentation process is usually accompanied either by chance contaminants or by added starter cultures. By chance contamination, successful products are not always produced.

Quite often semidry sausages are subjected to temperatures of 50–60°C in order to improve flavour and to inhibit bacterial development. To avoid excessive shrinkage, smoked sausages are removed from the smokehouse as and when they are properly smoked. Different diameter sausages need different smoking times.

The smoking temperatures required for different dry sausages vary from 12–22°C but never exceed 30–31°C. A temperature of 14°C is considered as optimum in dry sausage smoking. Some producers in Europe or the USA do not smoke their dry sausages at all but keep them for at least ten days to several months in a room in which the desired air conditions are obtained by various combinations of temperature, relative humidity and air circulation. Some sausages are lightly smoked before drying.

Drying or ageing is a key operation, especially in dry sausage production. The drying rate for dry sausages should be as low as possible. The most critical point in drying is to avoid the pronounced surface coagulation of proteins and the formation of sausage surface skin. If the sausages lose moisture too rapidly during the initial stages of the drying period, the surface becomes hardened and a crust or ring develops immediately adjacent to the casing. This hardened ring inhibits further transmission of moisture and the sausage has an excessively moist centre. Only a sufficiently wet and soft casing, a high relative humidity at the outset of the drying operation and the use of a lower relative humidity in the advanced stages of the process will permit moisture to migrate from the interior of the sausage into the outer layer. Thus, the sausage should dry from the inside outwards. If the outer layers of the sauage become hard, the diffusion of water will be inhibited and the sausage tends to spoil. In conclusion, if the drying rate is adequately slow the sausage casing will enable gradual drying.

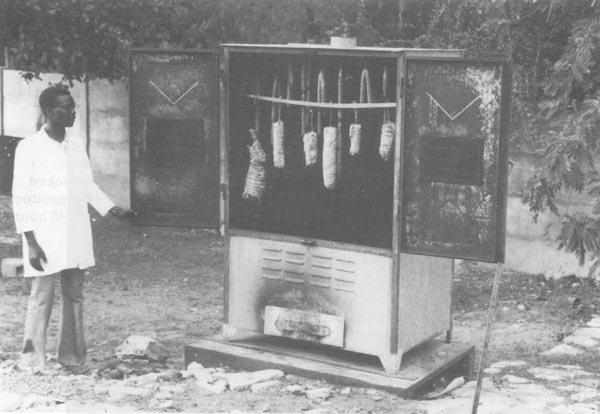

Fig. 26 SMOKING OF SAUSAGES IN MORNING AND EVENING HOURS IN TROPICAL CONDITIONS

At the start of the drying or the drying and smoking process, relative humidity can be as high as 98 percent. In the following 2–4 days the relative humidity must gradually but slowly be reduced. In that manner, the drying rate at the surface will be kept as low as possible. It is advisable to regulate the relative humidity according to the decrease in water-activity value of the product. Thus, the air relative humidity should be approximately 4 percent lower than the value of water activity of the product. For instance, when the water activity value of the product is 0.96, the optimum relative humidity of the smokehouse should be about 92 percent etc.

Too much humidity in the drying room favours the development of mould and sliming of products. Some producers do not object to a light white surface mould at the very beginning of the drying process. When fully developed, the mould is brushed off or, in some cases, washed. It is believed that mould contributes to the specific flavour of some products.

Sausages, produced in tropical climates, should be thoroughly dried, and smoked more heavily than products in the moderate climatic regions.

Sausage drying rooms should be equipped with a fan, and with facilities for dehumidification and chilling or warming the air, if necessary, as well as humidity and temperature control instruments.

In raw sausage manufacture, amongst the many factors involved, development of microflora and its effect on product quality plays a major part. The fermentation process in particular results in the desired flavour characteristics and tang.

In the traditional production process, fermentation is accomplished by natural flora. In order to achieve safe fermentation of the raw sausage, it is of importance to give the microflora the proper growth conditions as well as the appropriate type of the meat. One of a number of methods offered for choice are procedures requiring extended incubation times. For instance, the raw sausage mixture, containing meats, curing salts and sugar, can be placed in 15–18 cm deep pans and kept for 2–4 days at 3–4°C. After remixing, the mix is stuffed into casings and the drying process continued at 12–15°C with or without simultaneous smoking. A number of alternative procedures are found in practice.

The inherent bacterial sausage microorganisms use various sugar substances as energy sources, whereby they produce acids and contribute to the flavour of the raw sausages. While dextrose is degraded by almost all kinds of bacteria, lactose or starch products of higher molecularity are converted only by some of them. In the second case, the speed of acidification is delayed. Acidification, i.e. with a sufficiently low pH (below 5.2–5.3) is indispensable for adequate binding and colour development in the sausage. A pH value of 4.8 or below influences the taste, but does not contribute to better binding properties of the final product. However, this low pH gives fermented sausages excellent keeping qualities.

In general, addition of sugar varies from 0.3 to 2.0 percent. If dextrose or other easily degradable sugars are used, acidification is fast and the amount of sugar added should be somewhat lower. In opposition, corn syrup solid must be added at somewhat higher levels in order to compensate for its lower acidification properties.

A sufficient level of acidification can also be obtained by the addition of glutamine or some other acids and particularly by the addition of glucono-delta-lactone (GDL). When GDL is used, acidification (release of gluconic acid) occurs at 21–23°C. At GDL levels under 0.5 percent, the curing agent should be nitrate, but at GDL levels higher than 0.5 percent nitrite is preferred since too high a rate of acidification does not permit the process of denitrification performed by microorganisms.

Traditional fermentation of dry sausages in the pre-1940 period was performed as mentioned above by the inherent lactic acid-producing microorganisms or by back-inoculating a portion of recently fermented meat into the freshly prepared batch.

Fig. 27 RATE OF pH DECREASE IN FERMENTED SAUSAGES CONTAINING 0.5% DEXTROSE (D), 0.5% AND 0.8% GLUCONODELTALACTONE (g AND G) AND 0.5% STARTER CULTURE PLUS 1% CORN SYRUP (SC)

However, this practice was associated with many doubts and uncertainties and to overcome them, the use of starter cultures was introduced in the early 1940s. The manufacture of fermented sausages changed essentially, particularly with the use of frozen concentrated starter cultures.

Bacterial starter cultures used in the production of dry sausages are lactic acid producing and belong mainly to the general Lactobacillus, Pediococcus and Streptococcus. Besides a few French (ferments lactiques) and American preparations of lactobacilli (Lactacell MC, etc.), and Spanish mixed-culture preparations, those mainly used on the European market are the micrococci and lactobacilli. As a matter of fact the market today is dominated by three types of products: starter cultures containing micrococci, starter cultures containing a mixture of micrococci and lactobacilli and starter cultures containing lactic acid-producing cocci. The reason for applying these bacteria in the production of raw sausages is their ability to produce a consistent and controlled acidification able to inhibit growth of undesirable microorganisms and as an aid in obtaining the desired structure and colour of the final product.

Using starter cultures in current production practices, desired acidity can be achieved within 24 hours at a high (35–41°C) incubation temperature. This is in contrast to traditional manufacturing processes which utilized the natural flora of the meat as the source of lactic bacteria and required extended incubation times.

If stored in a warm hanging room, raw sausages shrink excessively and they become firm; if left in too humid or too cool a room, they soon lose their colour.

Most producers favour handling raw sausages, especially in warm weather, in temperatures around 18–22°C. This is done to avoid condensation which gathers on smoked sausages transferred from a cold to a warm place, such as the ordinary meat shop. Such condensation favours rapidly forming moulds.

It is impossible to cover all the numerous types and potential variants of fermented sausages in this manual but it is possible to indicate some of the major products and suggest methods suitable for the manufacture of exclusive warm climate products. A point which is necessary to make clear is that every successful sausage manufacturer has to spend some time to adjust his sausage formulations to suit local requirements. Table 3 gives basic and supplementary spices used in semidry and dry sausage manufacture. The use of nonmeat ingredients in fermented sausage manufacture is discussed under the heading “Nonmeat ingredients”.

Summer sausages are usually coarse-ground fermented products. They are produced under conditions that promote microorganism proliferation which imparts flavour and the desired keeping quality. Starter cultures may be helpful in obtaining quality products.

FORMULATION

Basic ingredients for 100 kg

55 kg lean beef

25 kg pork bellies

20 kg pork fat

Characteristic seasoning formula per 1 kg

30.0 g nitrite salt for curing

0.5 g sodium nitrate

3.0 g black pepper, coarsely ground

1.2 g coriander

2.0 g mustard seed

0.4 g garlic, fresh

0.4 g allspice

5.5 g dextrose

2.5 g sucrose (some sausage makers prefer to have excess sugar present in final products

which will produce the desired sweet flavour)

Casings

Pig casings: 35–45 mm in diameter

Processing and handling

The meat and fat are ground separately through a grinder plate having 5 mm holes. After thorough mixing, the sausage mixture is stuffed into casings. The sausages are tied into the desired length.

Further handling of sausages may differ. Sometimes they are fermented at 38°C and 95 percent relative humidity for 1–3 days. Fermented sausages may also be manufactured using a commercial lactic acid starter culture or 0.6–0.7 percent glucono-delta-lactone. The drying process is conducted until the desired degree of quality is reached.

This type of sausage is distinguished by high quality characteristics. The particularly attractive appearance as well as aroma and keeping quality are attributable to a low pH and low water activity. These sausages are predominantly pork products and, if stuffed in wide casings, they are known as dry salamis.

The use of glucono-delta-lactone (0.3 to maximum 0.5 percent) can improve the texture and colour of the product and accelerate production but the quality of the finished product will be somewhat lower.

FORMULATIONS

Basic ingredients for 100 kg

20–35 kg beef, well trimmed, prefrozen

30–45 kg pork (derived from older animals), well trimmed of fat, prefrozen

20–30 kg backfat and pork belly

20 kg beef, prefrozen at - 10°C

35 kg pork, prefrozen at - 5°C, well trimmed of fat

30 kg pork belly, prefrozen at - 5°C

15 kg backfat, prefrozen at -5°C

Characteristic seasoning formulae per 1 kg

30.0 g nitrite salt for curing

0.3 g potassium nitrate

2.0 g dextrose

4.0 g dry starch syrup

2.5 g ground white pepper

1.0 g white whole pepper

0.5 g coriander

30.0 g nitrite salt for curing

0.3 g potassium nitrate

2.5 g dextrose

2.5 g dry starch syrup

5.0 g lactose

3.0 g white pepper, ground

Casings

Corresponding diameters of artificial or natural casing

Processing and handling

The beef is chopped in the cutter to approximately 2–3 mm grain size and at the end of chopping all seasoning ingredients except salt are added and homogenized. Pork components are placed at a low cutter knife speed and coarsely chopped. Kitchen salt must be added at the very end of chopping.

The stuffed and tied casings are kept at 20–24°C with a high relative humidity (92–94 percent) for 24 hours. During the next 24 hours the relative humidity is reduced to 90 percent. In the course of the following 3–4 days, the temperature is gradually decreased to approximately 14–16°C as is the relative humidity. The rest of the ageing process is carried out at 14–15°C and 76–78 percent relative humidity.

The uncontrolled growth of “wild mould” should be completely stopped for hygienic reasons. Should a uniform white surface coat of mould be desired, immersion inoculation with mould starter cultures must immediately follow stuffing.

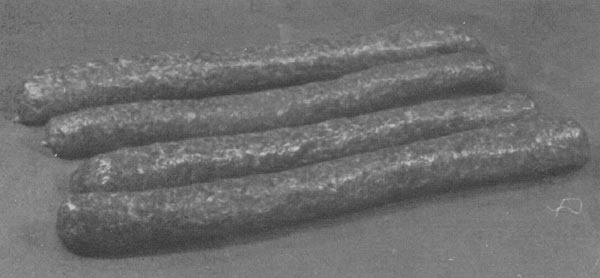

Fig. 28 ALL-BEEF AIR-DRIED SAUSAGES IN BEEF CASINGS PRODUCED IN HOT CLIMATE CONDITIONS

The name of this type of sausage is derived from the word “pepper”, indicating that pepper is used in its spicing. Pepperoni are often produced as an air-dried product. They can also be produced either as all-pork or all-beef products.

FORMULATION

Basic ingredients for 100 kg

50 kg pork trimmings

30 kg beef chucks, hearts, cheeks

20 kg pork jowl

Additional (nonmeat) ingredients

Addition of nonmeat proteins, such as whey or soy products to pepperoni mixture is sometimes practised.

Characteristic seasoning formulae per 1 kg

28.0 g nitrite salt for curing

0.5 g sodium or potassium nitrate

0.5 g chili

2.0 g allspice

1.5 g fenugreek

3.0 g ground pepper

4.5 g red pepper

1.5 g anise

10.0 g sugar

0.3 g peeled garlic

2.5 g dextrose

30.0 g nitrite salt for curing

1.2 g monosodium glutamate

4.0 g pepper

2.0 g red pepper

0.2 g chili

3.5 g dextrose

0.2 g garlic

Casings

Pig rounds: 28–32 and 35–44 mm in diameter

Processing and handling

Pork and beef are passed first through a 10–12 mm plate and then run through a 3 mm plate. The mixing and seasoning of meat is performed in a mixer for at least 5 minutes. The meat mixture may be then either cured in pans, 15 cm deep, for two days at a temperature of 2°C or immediately stuffed. After curing, the cured mass is remixed and stuffed into casings without delay and linked in pieces of 24–25 cm. The linked sausages are dried or smoked and dried. Drying is carried out according to consumer taste.

If the mixture is not cured in pans but stuffed directly into casings, the sausages are held for about 10 days at 3°C prior to placing them in a green room at 22–24°C with a relative humidity of 80 percent for 48 hours. Smoking is performed at 32–34°C for 2–3 days. The sausages are further dried at 14°C.

An alternative method, especially if starter culture is added, is to ferment stuffed pepperoni mixture for 24 hours at 35°C and dry it at 12–14°C for 4–5 weeks or until desired firmness is obtained.

Chorizos are a strongly hot spiced type of raw sausage, which can be sold and used as fresh (like merguez), semidry or dry sausages. Beef and fat, such as beef chucks, brisket fat and trimmed flank may be used in making an all-beef sausage variant.

FORMULATION

Basic ingredients for 100 kg

33 kg lean pork or lean beef

33 kg pork neck or beef flank

34 kg fat pork (jowl, belly, fat trimmings) or beef trimmings

Characteristic seasoning formula per 1 kg

28.0 g nitrite salt for curing

0.4 g potassium nitrate

0.8 g sugar

1.0 g garlic, fresh

2.0 g red pepper

1.5 g chili

0.5 g glucono-delta-lactone (optional)

Casings

Narrow and wide pig or sheep casings (28–38 mm)

Processing and handling

The pork components are run through the 6–9 mm plate. If beef is used, it is ground more finely (3–4 mm plate). During mixing, curing salts and sugar are added and the mixture cured either in a shallow pan at 4°C or in casings after stuffing. Sausages are divided into lengths of 8–10 cm.

After several smoking days (cold smoking at 14°C), the sausages are held at the same temperature until the desired texture is obtained.

An addition of 0.4 percent glucono-delta-lactone (if potassium nitrate has not been added in the mixture) will considerably accelerate the formation of desirable texture and contribute to a better keeping quality of the product (see “Nonmeat ingredients”).

Fig. 29 A SEMIDRY ALL-BEEF SAUSAGE PRODUCED WITH AN ADDITION OF 0.4% GLUCONO-DELTA-LACTONE, USING FORMULATION GIVEN IN THE INSTRUCTION FOR “PORK AND BEEF CHORIZOS”

There are several varieties of beef salamis, depending chiefly upon the length of the curing preblended sausage mixture, degree of fermentation, diameter of casings etc.

The acceleration of beef salami manufacture may be achieved by adding glucono-delta-lactone or 0.5 percent of a starter culture in the mixture before stuffing.

FORMULATION

Basic ingredients for 100 kg

75 kg beef chucks or other beef

25 kg beef brisket fat

Characteristic seasoning formula per 1 kg

25.0 g nitrite salt for curing

0.4 g potassium nitrate

0.5 g fresh garlic

2.5 g ground white pepper

2.0 g dextrose

1.0 g red pepper

0.2 g ginger

(lactic acid starter cultures may be added)

Casings

Beef middles or weasands

Processing and handling

The beef is run through a 4 mm plate of the grinder and the brisket fat may be diced. After mixing with other ingredients, the meat mass is placed in 15 cm deep pans for curing at 4°C for 15–48 hours. The mass is then remixed and stuffed into casings. Stuffing and tying must be very firm. The smoking is performed at gradually increasing temperatures, sometimes to 60°C or even more to stop the fermentation process. If a fully fermented product is preferred, the sausages should be hung for 3–5 days at 18–22°C, smoked in cold smoke for 2–4 days and dried according to demand. After smoking, the salami may be rinsed with water and then chilled.

To avoid the growth of mould, the sausages after removal from the smokehouse can be rinsed in hot water saturated with salt.

In traditional Near East meat processing, several groups of sausages can be found but beef sausages or “sucuk” are doubtlessly more typical and frequent. Sucuks are popular Turkish national products but they are manufactured throughout the Near East by numerous local sucuk markers. This type of product substantially differs from its European counterparts. Sucuks are exclusively beef products but occasionally buffalo meat and, more rarely, mutton are used.

Sucuks are sausages of roughly comminuted meat, mixed with fat and other ingredients, stuffed into sheep or beef casings and exposed to smoking and/or drying, including sometimes sun-drying. They are often annular shaped.

There are at least several types of sucuks which can be classified according to proportions of fat and lean, diameter of casing used, degree of drying etc. Sucuk production varies much depending upon the season.

FORMULATIONS

Basic ingredients for 100 kg

80 kg beef

20 kg beef or mutton fat

60 kg beef

30 kg mutton

10 kg fat

Characteristic seasoning formula per 1 kg

25.0 g salt or nitrite salt plus 0.5 g potassium nitrate

2.0 g black pepper

2.0 g red pepper

1.5 g garlic, fresh

1.5 g cumin

0.3 g cinnamon

0.4 g ginger

0.2 g cloves

2.0 g sucrose

Casings

Animal casings, mostly beef and sheep, 24–26 mm or more in diameter

Processing and handling

Prerigor meats are sometimes used in sucuk manufacturing. Meat grinding is very coarse (10 mm grinder plate is commonly used). All ingredients are thoroughly mixed together.

Casings for sucuk stuffing should be flushed inside with water just before use. Salted casings are washed free from salt before use and any casing that is left over should be resalted. Air-dried beef casings (air drying is the common method of beef casing preservation) must be free of any remnants of adhering fat. Artificial casings are also occasionally utilized.

The meat mass is sometimes chilled overnight and then firmly stuffed. The stuffed sucuks are often pressed under boards by means of weight.

The sausages can be smoked several days or several weeks. In fact, the drying process lasts 2–3 weeks or more, depending on casing size. Air circulation is sometimes so high that sausages, particularly if the casings contain remnants of fat, very often acquire a slightly rancid tallow flavour. Intensive fermentation, which occurs rapidly during the first days of drying, nearly stops at the end of the process. For more details on processing and sucuk handling, see the instructions for “Pork and beef chorizos”.

The addition of 0.4 percent of glucono-delta-lactone in the sucuk mixture can considerably reduce production time and improve the keeping quality of the finished product.

The usually accepted quality requirements for European semidry or dry sausages (flavour, colour) are often neglected by sucuk consumers. The most popular sucuk flavour is a specifically balanced mixture of fermentation products, added spices and components of fat and meat degradation. Very often the strongly accentuated garlic flavour and more or less fermented and, to some extent, rancid sucuk taste may be unpleasant to unaccustomed people.

Fig. 30 BEEF RING-SAUSAGES OR SUCUKS ARE USUALLY STUFFED IN BEEF CASINGS

WHICH MUST BE FREE OF ANY REMAINDER OF ADHERING FAT.

ON THE CONTRARY, THE AIR-DRIED SAUSAGE MAY BECOME RANCID

AND HAVE A POOR APPEARANCE

(Photo courtesy of Dr M. Marinkov)

“Landjaegers” or hunter's sausages are the flat dry sausages, made by stuffing a mixture of beef, pork and seasonings into a medium diameter casing and cutting the stuffed casings in desired lengths. The characteristic operation is pressing, usually in wooden moulds, to flatten the sausage. A possible alternative in the production of these sausages for tropical regions is to use all-beef ingredients.

FORMULATIONS

Basic ingredients for 100 kg

35 kg beef (may be held at - 10°C for 2–3 days)

65 kg pork bellies (- 10°C for 2–3 days)

70 kg beef

30 kg pork backfat (may be held at - 10°C for 2–3 days)

all-beef landjaegers

75–80 kg beef

15–25 kg beef fat

Casings

Pig or sheep casings, 26–34 mm in diameter

Processing and handling

The beef is coarsely ground or directly chopped and then worked to a mass with usual additions (salt and seasoning). At the very end of chopping, the pork components are incorporated. The mix is stuffed into pig or sheep casings, cutting the stuffed casings off in about 30 cm lengths and then placing the sausages in wooden moulds. The sausages are pressed into the moulds by hand where they take on their flat shape and each link is separated into two identical sausages connected together by a section of empty casing. Depending upon the force of pressure the sausages are produced in different thicknesses.

The landjaegers are allowed to remain in the press for 1–2 days at about 20–24°C or for about 2–3 days at approximately 18–20°C, giving sufficient time for biochemical and microbiological processes and for obtaining the required flat shape. The shaped sausages are then removed from the moulds, placed on smoke rods and hung for 3–4 days in a cold room (16–20°C) for surface drying and further “ripening”. The sausages are then given a cold hardwood smoke overnight or a little longer.

From the smokehouse, the sausages are taken again to the drying room for half a day and then stored or packed.

Freshly stuffed sausages are 6 to 7 pairs to a kilo; and the finished product about 9 to 10 pairs to a kilo. Shelf life is at least 60 days.

The following is a list of basic formulations for selected large- and small-diameter fermented sausages which are known as a traditional dry product (Table 7).

| Sausage | Beef % | Pork % | Pork backfat % | Spices1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large diameter (salami) | ||||

| German type | 65–75 | 25–35 | coriander, garlic | |

| Italian type | 30 | 45 | 25 | ginger, garlic |

| Hungarian type | 70 | 30 | red pepper, nutmeg, cardamom, garlic | |

| Polish type | 10–15 | 55–60 | 25–30 | marjoram |

| Small diameter | ||||

| salametti (28/32 mm) | 30 | 40 | 30 | |

| garlic sausage | 50 | 20 | 30 | red pepper (hot), |

| (24/28 mm) | rosemary, garlic | |||

| beef garlic sausage | 80 | 20 | fenugreek, red pepper, | |

| (24/28 mm) | (beef fat) | ginger, garlic |